While preparedness, alerts and warnings, and other measures of heat action plans have vastly reduced the impact of heat waves, the duration and frequency of climate-induced heat waves are on the rise. Jency Samuel says that as heat waves impact people’s health and livelihood, and the nation’s economy adversely, there is a need to improve and better implement the heat action plans.

The World Meteorological Organization announced in mid-May this year that global temperatures would increase to record levels in the next five years, caused by greenhouse gases and El Nino. In April this year, the world has witnessed how lives were impacted in India and many South Asian and Southeast Asian countries owing to intense heat waves.

Consequently, the high temperatures continued in May and June, as recorded at some places in India. An update on this shows the temperature rise across few cities. On 23rd May, Delhi recorded 45°C. During May, temperature recorded in Chennai was around 40°C or more and the same condition lasted for more than two weeks; and incidentally the same weather condition continued till almost the middle of June 2023 as on June 20, 2023. In May, Jaipur recorded 40°C or more at a stretch for 11 days. In June, Lucknow recorded 40°C or more consecutively for 14 days as on June 20.

This would be exacerbated as a recent multi-country study has revealed that the likelihood of human-induced climate change causing such heat waves is 30 times higher.

What is a Heat Wave?

“Heat wave is a period of abnormally high temperatures, more than the normal maximum temperature of a place,” is how the National Disaster Management Authority defines it.

“Normal temperature refers to a 30-year average. Every day the temperature of a place is recorded. The normal temperature of a particular day, let’s say June 15, is calculated by taking the average of the temperatures recorded on June 15 over 30 years,” says Dr S Balachandran, the head of Regional Meteorological Centre, Chennai, one of the centres of the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD).

The entire discourse on heatwave happens on the basis of certain criteria comprising the temperature range. “If the maximum temperature of a place reaches at least 30°C for hilly regions, 37°C for coastal regions, and 40°C for interior plains, then it is considered as heat wave. That is the threshold value,” adds Dr Balachandran. “One of the criteria is, if the departure from normal temperature is 4–6°C, it is considered a heatwave and when it exceeds 6°C, it is considered a severe heat wave.”

The other criterion is to consider the actual maximum temperature. If the temperature is 45°C or more, it is a heat wave condition, and if it is more than 47°C, it is a severe heat wave condition.

What Causes a Heat Wave?

Winds generally cause the circulation of air. But sometimes it gets trapped due to high pressure, which happens commonly in summer. “Depending on the direction in which air circulates, we call it cyclonic circulation (it is not a cyclone) and anticyclonic circulation. Anticyclonic circulation involves high pressure accumulating over an area and sinking of air towards the ground. When air comes down, it gets compressed,” says Dr Balachandran.

The air also heats up as it sinks. For every 100 metres the air sinks, the temperature increases by 1°C. “The sinking air acts like a dome and prevents vertical movement of air. The conditions lead to loss of moisture in the air and cloudless skies. Without the clouds, the sunlight hits the earth directly,” says Dr Balachandran. “In coastal regions, sea breeze and land breeze play a role. When land breeze, which blows from the land to the sea in the morning, is stronger, sea breeze cannot blow into the land in the evening. This results in prolonged heat over the land.”

Various factors combined together may result in heat waves. But qualitatively heat wave is a condition of air temperature which becomes fatal to human body when exposed (Source: IMD).

Impact on Health

Heat waves have been increasing across the globe, which has immensely impacted lives. Between 1998 and 2017 more than 166,000 people died due to heatwaves, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

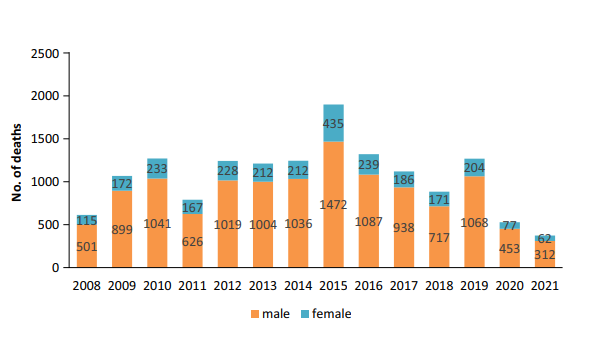

In 2021, in India, out of the 7000-odd accidental deaths caused due to forces of nature, 374 deaths happened due to heat/sunstroke, as per the report of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). Between 2015 and 2019, 20 transgenders lost their lives, as per the NCRB data (which is not indicated in the chart below). Many argue that the NCRB data does not truly reflect the heat- related mortalities. This also raises the issue of unreported data, and therefore the data reported in NCRB may not reflect the real life scenario in its entirety.

“In India, normally heatwaves occur in the northwest—from Rajasthan to Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh—and in Odisha, Andhra Pradesh in the east. This is the core heat wave zone,” says Dr Balachandran.

Among the states heat/sunstroke was the dominant cause in Telangana, where 43 of the 112 accidental deaths occurred due to forces of nature—heat/sunstroke, as the state falls in the core heat wave zone. In 2020 also, Telangana had the most heat/sunstroke deaths among the states, with 98 deaths.

A team of researchers at Banaras Hindu University analysed monthly, seasonal and decadal variations along with long-term trends of heat waves and severe heat waves for pre-monsoon (March–May) and early summer monsoon (June–July) season during 1951–2016 and found a southward expansion in heat wave events, explaining the mortality in Odisha and Andhra Pradesh as well.

Heat waves result in many illnesses such as heat cramps and hyperthermia, besides making chronic illnesses worse, according to WHO. While such is the impact on human health, heat waves cause a host of other problems as well.

Impact on Agricultural Sector

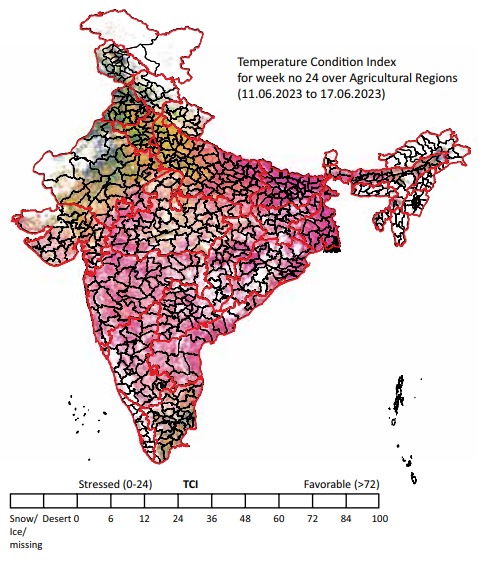

The Agriculture Meteorology Division of IMD, Pune, offers regular weather reports for the benefit of the farm sector. The division calculates the Temperature Condition Index (TCI), which is used to indicate the stress on vegetation caused by temperature and extreme wetness. While the TCI remained favourable across most states in the first week of April, it had become stressed by the third week of June, as shown in the figure, indicating the likely adverse impact on crops.

According to State of the Global Climate 2022 report, published by World Meteorological Organization, pre-monsoon period was exceptionally hot in India, and grain yields were reduced by the extreme heat. Not only were the maximum temperatures higher in many states in March and April last year, but the minimum temperatures were also higher. This led to reduced yields in many states.

In Punjab, the heat wave events led to yellowing and shrivelling of wheat grain, besides forced maturity, resulting in up to 25 per cent reduction in yield, according to Heat Wave 2022, a report published by Indian Council of Agriculture – Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture (ICAR-CRIDA). The increased temperature also led to whitefly infestation, reducing green gram yield by up to 20 per cent. Some districts in Punjab had an increase in fall army worm attack. This study also reports reduced yields in maize in Punjab, chickpea in Himachal Pradesh, besides wheat and chickpea in Haryana and Madhya Pradesh. In Uttar Pradesh, reduced yields were recorded in wheat, cow pea, and mustard. Horticultural crops including lemon, mango, onion and cauliflower were impacted in Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Marathwada, and Rajasthan.

Impacts on Economy

Such widespread impact on crops naturally impacts the economy. It is a vicious circle cycle of scarce water, increased electricity needs for cooling purposes, increased public health expenditure, and reduced labour productivity. Socioeconomic factors play a critical role in the extent of the impact.

“Heat waves affect the vulnerable citizens and people such as vendors, construction workers and farmers, who work outdoors,” said Dr Emmanuel Raju, Copenhagen Center for Disaster Research at the University of Copenhagen, and one of the authors of the World Weather Attribution study, during a media briefing.

Assuming a global temperature increase of 1.5°C by the end of the 21st century, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that by 2030, 2.2 per cent of total working hours will be lost due to heat stress. Among the South Asian countries, India is affected the most by heat stress, which lost 4.3 per cent of working hours in 1995 and is projected to lose 5.8 per cent of working hours in 2030.

Given the region’s role as an economic hub for manufacturing, the impact of extreme heat events propelled by climate change will be highly disruptive to the economies in the region, with global implications.

The Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) Asia-Pacific Disaster Reports 2021 and 2022 estimate that in Asia, the annual investment in adaptation would need to be highest for China, at USD 188.8 billion, followed by India at USD 46.3 billion, and Japan at USD 26.5 billion. As a percentage of the country’s GDP, the highest cost is estimated for Nepal, at 1.9 per cent, followed by Cambodia at 1.8 per cent, and India at 1.3 per cent.

The Climate Change – Heat Wave Connection

Following the heat waves in India and South Asian countries, World Weather Attribution (WWA), which is an international group of climate scientists, analysed the event. The scientists analysed weather data and computer model simulations to understand the impact of climate change on the Asian heatwave. They analysed the average maximum temperature and maximum heat index for four consecutive days in April across south and east India and Bangladesh. The heat index is a measure that combines temperature and humidity and reflects more accurately the impacts of heatwaves on the human body. According to their study, human-induced climate change made April’s humid heatwave in India—besides in Bangladesh, Laos and Thailand—at least 30 times more likely.

Another analysis by Climate Central, an organization that simplifies and communicates climate science, after the three-day extreme heat event in Uttar Pradesh between June 14 and June 16, 2023, showed that the heat wave was made at least two times more likely by human-induced climate change. The Climate Central analysis uses Climate Shift Index (CSI), which quantifies how climate change contributes to daily temperatures.

“CSI goes from –5 to +5. A score of 1 indicates that the temperatures are 1.5 times more likely because of climate change. We use level one as a threshold for detectability. Level 2 indicates conditions are two times more likely, and so on,” observes Dr Andrew Pershing, Director of Climate Science at Climate Central.

Besides Uttar Pradesh, most locations across India experienced significant CSI levels during the same period. “We usually use CSI 2 as the basis to indicate significant level. India has had strong CSI signals for more than a month. The western coast including Mumbai and Goa have had lots of days with CSI 5,” notes Dr Pershing.