Designed to help address the millions of customers who remain underserved in Nigeria, the undergrid model has wide-reaching implications for countries – worldwide – particularly countries like India, where reliable last-mile supply of electricity continues to be a challenge.

Innovation in utility business models is more important than ever as underserved rural customers increasingly demand clean, affordable, and reliable electricity service. In one Nigerian community, a new model for optimizing rural supply can provide valuable insights for communities around the globe. In particular, power sector similarities in growing global economies like India and Nigeria offer a chance to exchange ideas and explore alternative business models.

The new undergrid minigrid in Mokoloki, Nigeria, offers one such innovative model for meeting rural electricity demand with reliable power supply. The minigrid was implemented through a collaborative approach that enables a privately owned solar minigrid to serve a community within a distribution company's territory. Lessons from this new model—shown to be technically, politically, and economically feasible in Nigeria—could be the key to a resilient, reliable grid in India and elsewhere.

The Challenges of Rural Electrification

Traditional grid networks are an inadequate solution to providing reliable power supply in countries with large and dispersed rural populations. For example, despite recent large-scale electrification in both India and Nigeria, over 80 million people remain unserved and nearly 200 million underserved (without reliable, high-quality power. Technical and economic challenges make it difficult for large utilities to provide adequate customer service, metering, billing, collection, and reliable power in rural areas—where a combination of strategies are required for electrification. The adoption of new business models is key for electric utilities in these remote rural areas to economically provide reliable supply and customer services.

Despite great advances in rural electrification by the Government of India, electric utilities are unable to ensure high-quality service across the country. Technically, distribution networks now access 100 percent of the inhabited census villages, and only about 0.8 million "unwilling" households have not accepted electricity connections. However, electricity distribution companies are experiencing both logistical and financial challenges resulting in poor reliability and quality of supply in rural areas. Adding to the expense of distributing electricity to less-dense rural populations, distribution companies report extremely high aggregate technical and commercial losses of up to 40 percent. Annually, US$13 billion (one lakh crore) of electricity service is never even billed.

Similarly, rural Nigerian communities often struggle to access reliable grid power. There is insufficient generation, transmission, and logistical capacity to consistently serve remote rural customers. At the same time, distribution companies are losing approximately $0.21 (INR 16) per kWh distributed in rural Nigeria. However, a new pilot addresses the technical and economic challenges of traditional grid service. The new undergrid minigrid project by Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) and partners marks a milestone in terms of distributed energy resources (DERs) and demonstrates a replicable model for rural electrification.

Undergrid DER Solutions

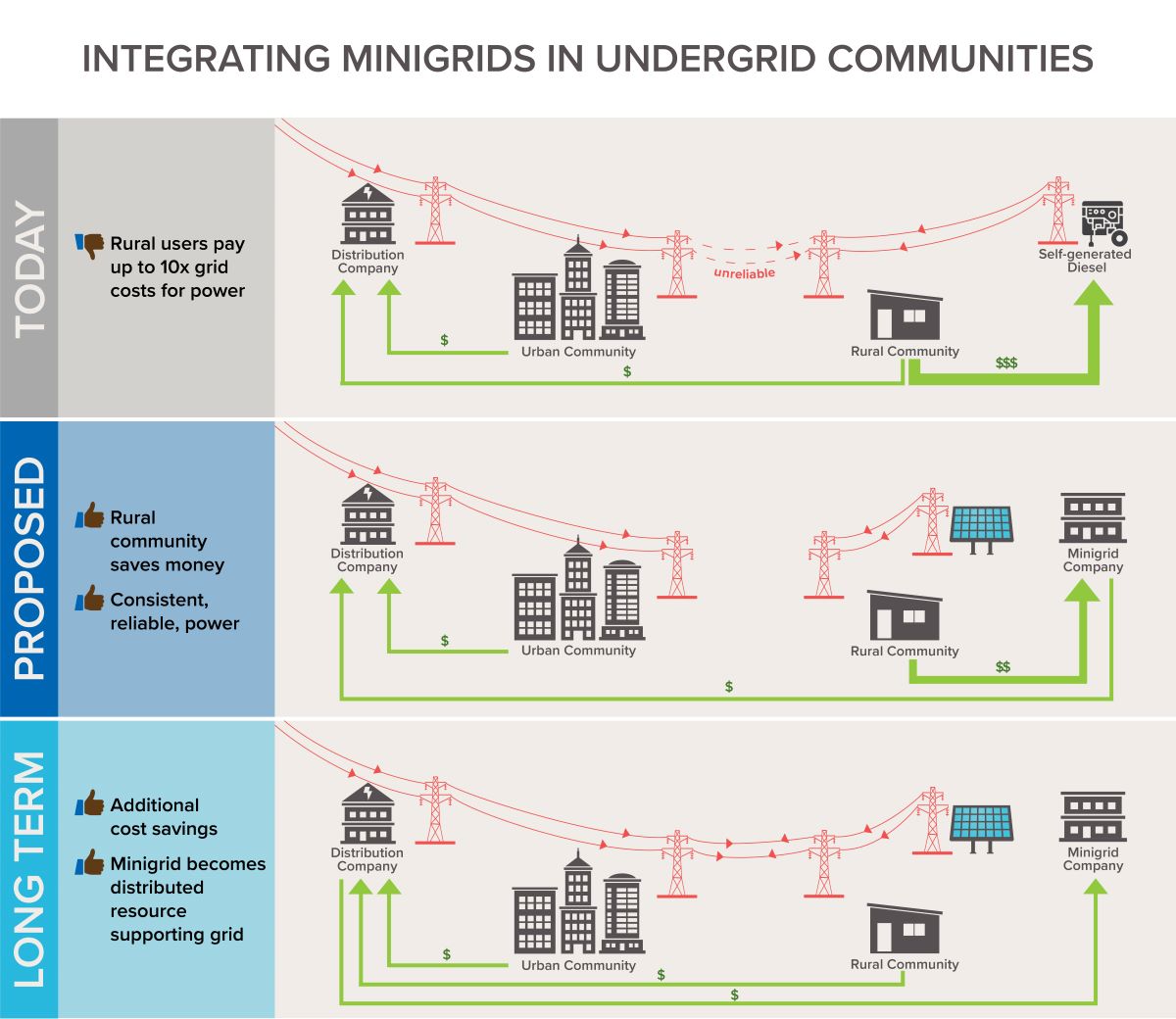

This undergrid minigrid pilot in Mokoloki, Nigeria, provides reliable last-mile service to undergrid customers—those who are connected to the main electric grid but receive unreliable or no electricity service. Undergrid minigrids share the distribution infrastructure belonging to a distribution company, versus fully interconnected (grid-tied) minigrids that exchange power with the distribution company, buying and selling electricity. The new model enables the sharing of assets between utilities, private developers, and communities to provide more efficient, reliable service and a net economic gain. The minigrid developer takes on the responsibility of service to the community, paying the utility a small usage fee for the right to provide service and sharing of the distribution infrastructure.

The Mokoloki project was made possible by collaboration between Ibadan Electricity Distribution Company, Nayo Tropical Technologies, and Mokoloki community leaders with support from RMI and the Nigerian Rural Electrification Agency (see the project summary). The project demonstrates that undergrid minigrids are viable in the Nigerian context. Designed to help address the millions of customers who remain underserved in Nigeria, the undergrid model has wide-reaching implications for countries – worldwide – particularly countries like India, where reliable last-mile supply of electricity continues to be a challenge.

The new undergrid minigrid project in Nigeria provides reliable last-mile service to underserved customers.

The Government of Nigeria has enabled this particular undergrid minigrid approach to succeed through its Mini Grid Regulation, which is fairly light-handed and enables utilities and private sector developers to explore new business models. It specifically provisions for interconnected minigrids, eliminating minigrid-utility competition within a single community.

Translating the Undergrid Approach to India

For the 100 million rural Indian households experiencing unreliable electricity supply, undergrid minigrids and other distributed energy resource models could inject vital stability. In addition to their core service, minigrids can drive community resilience and help traditional utilities reduce their losses and better serve rural areas. The new minigrid in Mokoloki is already strengthening local healthcare delivery, enhancing agricultural opportunity, and attracting businesses. These same attributes are also targeted under the Indian government's policy and program goals.

Today, inefficient electricity solutions, like minigrids operating on redundant distribution networks in grid-served communities, indicate a need for more integrated minigrid models in rural India. Despite growing interest in DERs, there may still be regulatory and other barriers to overcome.

With each state in India implementing state-specific regulation on minigrids within a broad national framework—the Central Electricity Authority's Technical Standards for Connectivity of the Distributed Generation Resources, 2013 and the subsequent Amendment in 2019—some states are more ready for this novel solution. For instance, states like Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha have policies that enable the interconnection of minigrids with the main grid. However, for the undergrid minigrid model to succeed, the redundant networks seen today must be eliminated by state or national regulation that clearly assigns the mechanism for minigrids to use existing distribution networks and buy or sell power to the grid.

There is a strong economic case for minigrid service in rural India due to its greater financial viability. Today, distribution companies see an average revenue gap of around $0.01 (INR 0.45) per kWh up to $0.03 (INR 2) in some areas. The Mokoloki pilot proved that, in Nigeria, customers are willing to pay two to five times more than grid tariffs for electricity that is clean and reliable and offers stable voltage, all with good customer support. The increased cost (necessary for smaller-scale minigrid systems) is offset by improved power quality and reduced expenditures on energy alternatives, like candles, batteries, kerosene, and fossil-fueled generators.

Similarly, in India, even poor customers are willing to pay more for increased power reliability. Finally, to enhance their cost-competitiveness as well as to create job opportunities, minigrids could provide additional niche services like productive use programs that use electricity to generate income by adding value to products or services.

Innovative minigrid design can provide greater economies of scale, higher operational efficiency, more affordable electricity, and improved service quality in India. For instance, minigrids of 1–2 MW capacity could cover a cluster of villages—replacing smaller individual systems.

As in the Nigerian pilot, minigrids can use already-installed distribution networks (through lease or other arrangement with the distribution companies) to reduce infrastructure redundancy. They can sell power to and purchase power from the grid to further improve revenue and reliability. And, minigrids can also offer productive use services such as irrigation, small commercial applications, and electric mobility to enhance their service. Through minigrid partnerships, Indian distribution companies can reduce their losses and improve customer service much as their Nigerian counterpart is doing in Mokoloki.

The Opportunity for Co-Learning

Because India's energy sector development is more advanced, there are opportunities for continuing to share lessons to and from countries like Nigeria. As illustrated, the undergrid minigrid pilot in Nigeria demonstrates a short-term ‘proposed' solution that uses an islanded system to provide reliable, affordable service. In the long run, these systems would likely become fully interconnected to the grid — as we are proposing for India. Early interconnected undergrid minigrids in India could learn from the intermediate process in Nigeria, while also offering lessons for the future state of the grid.

Next Steps

The following actions will help to further explore the undergrid minigrid model's feasibility in India:

- Assess local customer willingness to pay more for minigrid-style service, including factors around reliability, voltage stability, and customer service.

- Conduct cost estimates for interconnected minigrids, which might serve multiple communities or exchange power with the main grid to improve the cost-benefit ratio.

- Develop a light-handed regulatory framework for minigrids and the necessary rules within which interconnected minigrids would operate.

- Support distribution companies to explore innovative business models with private sector partners—for instance, through the Discom Transformation Platform—that enable distribution sharing with a minigrid partner and are suited to the Indian political economy.

- Implement pilot projects that test the interconnected undergrid minigrid model.

- Share the lessons learned from early interconnected undergrid minigrid projects through different platforms such as the Distribution Utilities Forum to enable replication domestically and abroad.

India has pioneered isolated minigrids since the early 1990s. Innovations in technology, DERs, and the use of smart technologies are becoming the norm rather than the exception for new rural electrification projects. To continue that trajectory, early interconnected minigrids in India can learn from the process in Nigeria while also offering lessons for the future state of the grid. And, as these approaches drive reliability, quality and financial viability in the electricity sector, this opportunity could put India at the forefront of new techno-business model development.

(Sachi Graber is a former Senior Associate with RMI's Africa Energy program and James Sherwood is a Principal in the same program. This blog was originally published by the Rocky Mountain Institute on its website.)