Ahead of World Wetlands Day 2026, the Centre announced two more wetlands to India’s list of Ramsar sites, taking the national count to 98. Recognition matters.

But protection without sustained finance rarely translates into restoration on the ground. Desilting channels, restoring hydrology, controlling invasive species, compensating local communities, and monitoring ecosystem health over decades require resources that annual budgets alone cannot provide. At a time when climate impacts are intensifying, India must urgently look beyond forests and recognise wetlands and peatlands as a critical, and currently underutilised, pillar of high-integrity carbon finance.

India has no shortage of wetlands. National assessments indicate that wetlands cover over 15 million hectares, cutting across floodplains, high-altitude lakes, mangroves, lagoons, marshes, and urban water bodies. Yet these landscapes are among the most degraded ecosystems in the country. Encroachment, pollution, altered river flows, infrastructure expansion, and drainage have steadily eroded their ecological character. The climate cost of this neglect is rarely acknowledged: degraded wetlands lose their ability to store carbon and regulate water, and in some cases become net emitters of greenhouse gases.

Peatlands illustrate this risk most starkly. Though they occupy relatively small areas, peatlands store enormous amounts of carbon accumulated over centuries. When intact, they act as long-term carbon sinks; when drained or disturbed, they release carbon continuously for decades. India’s peatlands remain poorly mapped and institutionally invisible, spread across Himalayan regions, coastal systems, and select inland wetlands. Emerging research suggests their extent and climate relevance are far greater than previously assumed. Ignoring them is not a neutral choice. It is a slow but persistent climate liability.

Carbon finance offers a practical way to reverse this trend, provided it is approached with rigour rather than enthusiasm alone. Globally, carbon markets are moving beyond tree-centric models to include wetland restoration, tidal ecosystems, and peatland rewetting. India is well positioned to engage with this shift. The question is not whether wetlands and peatlands can generate carbon value, but whether India is willing to design systems that reflect their ecological complexity.

One danger is the temptation to treat carbon credits as a quick fix. Wetlands are dynamic hydrological systems. Their carbon outcomes depend on water depth, salinity, seasonal flooding, vegetation type, and methane dynamics. Applying generic project templates risks generating credits that satisfy paperwork but fail to deliver long-term climate benefits. Another risk is overlooking social context. Wetlands support fisheries, grazing, agriculture, and cultural practices. Excluding communities in the name of carbon would undermine both equity and permanence.

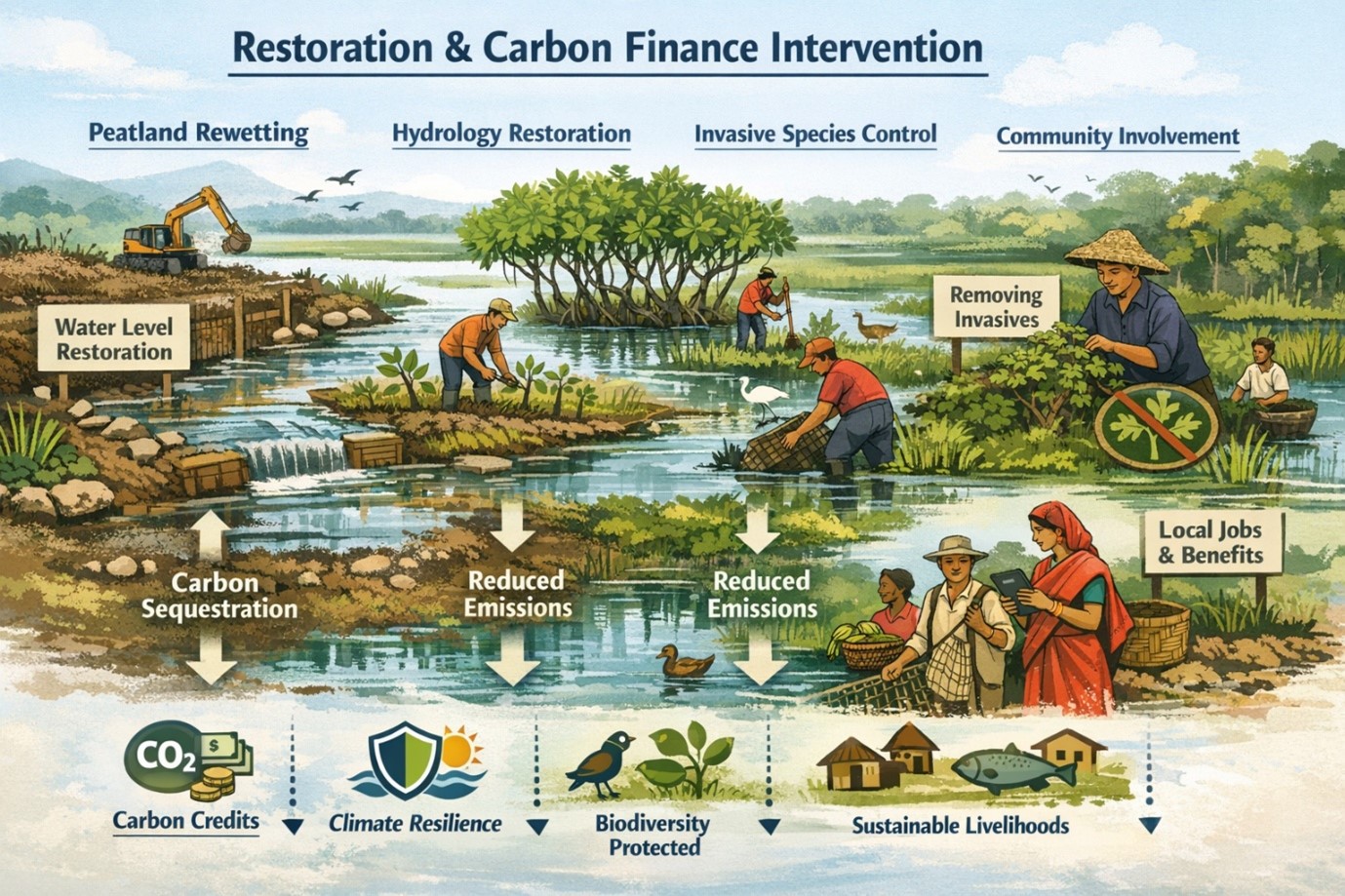

This is why context-specific carbon standards are crucial. Internationally recognised methodologies now exist for tidal wetland restoration, mangroves, seagrass, and peatland rewetting. These frameworks (Figure 1) explicitly address hydrology, methane emissions, leakage risks, and permanence, which are issues central to wetland systems. India does not need to reinvent standards, but it does need to adapt them to its ecological diversity and governance realities. A Himalayan peatland, a deltaic mangrove, and an urban floodplain cannot be treated through the same carbon lens.

Figure 1: From Restoration to Revenue Carbon Finance Pathways for Wetlands & Peatlands

Technology can bridge the gap between ecological nuance and financial credibility. Wetlands are difficult to monitor through traditional field surveys alone, but advances in Earth observation have changed the equation. Radar satellites can track inundation dynamics even under cloud cover. Optical data can monitor vegetation health and stress. Time-series analysis can distinguish seasonal variation from degradation. When combined with targeted field measurements, such as water table depth or soil organic carbon, these tools allow for credible, cost-effective Measurement, Reporting and Verification (MRV).

Artificial intelligence and machine learning can further reduce transaction costs by automating wetland classification, detecting encroachment or drainage, and flagging anomalous changes that require field verification. Importantly, technology should not replace people. Community-based monitoring using mobile tools, geo-tagged photographs, and participatory water-level logging can strengthen transparency while ensuring local stakeholders remain central to project governance. In carbon markets increasingly sensitive to integrity and social safeguards, such hybrid MRV systems are no longer optional.

If India is serious about unlocking wetland and peatland carbon finance, four strategic steps are urgent.

First, the country needs a carbon-oriented wetland and peatland inventory. Existing wetland maps focus on spatial extent, not carbon stocks, drainage status, or emission risk. A national inventory that identifies priority peatland zones, degraded wetlands suitable for restoration, and high-risk emission hotspots would provide the foundation for credible project development and policy planning.

Second, India should invest in a small number of high-quality pilot landscapes rather than dispersing effort thinly. Demonstration projects across representative systems, such as coastal mangroves, riverine floodplains, high-altitude wetlands, and peri-urban lakes, can help refine methodologies, test MRV frameworks, and establish realistic cost-benefit models. These pilots should prioritise integrity and learning over rapid credit issuance.

Third, methane and biodiversity safeguards must be treated as core design elements, not inconvenient side notes. Wetland restoration can alter methane emissions in the short term even as it delivers long-term climate benefits. Robust accounting, conservative crediting, and transparent disclosure are essential to maintaining trust. At the same time, projects must protect ecological character, in line with Ramsar principles, rather than simplifying wetlands into carbon factories.

Finally, carbon finance must be anchored in local institutions and livelihoods. Wetlands are not empty spaces. They are working landscapes. Benefit-sharing mechanisms must be explicit, equitable, and enforceable. Without community ownership, even technically sound projects will struggle to endure.

India stands at a strategic crossroads. As climate impacts intensify and global carbon markets demand higher integrity, wetlands and peatlands offer a rare convergence of mitigation, adaptation, biodiversity conservation, and livelihood support. Treating carbon finance in these ecosystems as a national priority is not about chasing a new revenue stream. It is about correcting a long-standing imbalance in India’s climate strategy.

Forests will remain central to nature-based solutions. But the next frontier lies in the water-logged, seasonally flooded, often overlooked landscapes that quietly buffer floods, store carbon, and sustain communities. If India can integrate technology, context-specific standards, and inclusive governance, wetlands and peatlands could become one of its most credible and climate-resilient carbon assets. The opportunity is real, and the cost of delay is rising.