Rajaji National Park is a magnificent ecosystem nestled in the Shivalik range and the beginning of the vast Indo-Gangetic Plains, representing rich floral and faunal diversity. The Park constitutes an important repository of the wild fauna and the last refuge of a number of threatened animal species in the lesser Himalayan zone and upper Gangetic plains. Considering the abundance of nature's bounties heaped in and around the Park, the area attracts a large number of wildlife conservationists, nature lovers, and eco-tourists. On the occasion of International Day for Biological Diversity (May 22), Dr Ritesh Joshi and Kanchan Puri have expressed their views about the wilderness and biodiversity of the Rajaji's landscape, which is also a haven for Asian elephants.

The world famous Rajaji National Park was established in the year 1983 with the aim of maintaining a viable population of the Asian elephants. The Rajaji National Park is one of the crucial wildlife habitats in the state of Uttarakhand, forming the northwestern limit of the range of Asian elephants and tigers in India. The Park has been designated as a reserved area for 'Project Elephant' by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, to strengthen the management and conservation activities. The Park was notified as Rajaji Tiger Reserve in the year 2015, making it the 48th Tiger Reserve in the country and second in Uttarakhand. Declaring Rajaji National Park as the Tiger Reserve is noteworthy because it sustains a wide range of endangered animals in upper Gangetic plains, especially the Asian elephants and tigers. Besides, the reserve has a great conservation value, as it is an important part of Terai-arc landscape between Yamuna and Sharda rivers, which is known as Rajaji–Corbett Tiger Conservation Unit, having an area of about 7500 km2.

Even though the park was established in 1983, final notification for the park was issued in the year 2013 because of non-settlement of rights of the local people and several other legal problems. Further, in the year 2002, this elephant range was also designated as the 11th Elephant Reserve in the country, and was named as the Shivalik Elephant Reserve, with an area 5405 km2. In addition to the existing core area of 820.42 km2 of the Rajaji National Park, few portions of Laldhang and Kotdwar forest ranges of the Lansdowne Forest Division and Shyampur forest range of the Haridwar Forest Division, which is 255.63 km2, have been merged under the Rajaji Tiger Reserve, making it 1076 km2 area.

Rajaji National Park falls under the tropical moist and dry deciduous forest type and upper Gangetic Plains biogeographical zone. The reserve constitutes an important repository of the wild fauna and is the natural heritage of Uttarakhand and the last refuge of a number of threatened animal species. This can also be attributed to a wide altitudinal range and presence of the River Ganga, flowing across the reserve. The reserve holds about 49 species of mammals, 28 species of serpents, 12 species of turtles/tortoises, nine species of lizards, 10 species of toads and frogs, 49 species of fish, and more than 300 species of birds. Diverseness of floral and faunal species and high probability of sighting of the elephants have always attracted the researchers and tourists to stay connected with the reserve. Records of the Rajaji National Park reveal that the number of foreign and national tourists has increased in recent years. During the years 2000–2001, nearly 5800 tourists enjoyed wildlife safari in Rajaji National Park, which generated a revenue of `172,625 ($2447.71). However, during the years 2015–2016, nearly 45,590 tourists visited the Rajaji National Park, from which a revenue of `10,202,739 ($144,668.41) was received.

Some of the dominant floral species of the reserve are Shorea robusta (sal), Mallotus phillipinensis (kamala), Acacia catechu (cutch), Haldina cordifolia (kadam), Terminalia bellirica (bahera), Ficus benghalensis (Indian banyan), and Dalbergia sissoo (Indian rosewood). Elephant is the flagship species of the reserve and other wild animals found in the reserve include Panthera tigris (tiger), Panthera pardus (leopard), Ursus thibetanus (Himalayan black bear), Melursus ursinus (sloth bear), Hyaena hyaena (hyaena), Muntiacus muntjak (barking deer), Naemorhedus goral (goral), Axis axis (spotted deer), Rusa unicolor (sambar), and Sus scrofa (wild boar). Among reptilian fauna, the Crocodylus palustris (mugger crocodile) and Ophiophagus hannah (king cobra) represent Rajaji's faunal diverseness. This protected area is one of the important wildlife habitats in northwestern Shivalik landscape, which also forms the northwestern distribution range of the tigers, elephants, and king cobra in the country.

Rajaji National Park is one of the potential sites to observe wild elephants in their natural habitat. As per the recent estimates carried out by the Uttarakhand Forest Department in the year 2015, Uttarakhand harbours nearly 1800 elephants, which are distributed within 14 protected areas, including reserve forests. Interestingly, these population estimates indicate that there is a marginal increase in the number of elephants over the years. The estimation also reveals that Rajaji National Park has been maintaining a stable population of the elephants for the last 1.5 decades, which averaged 394.5±71.90 (range 302–469). While working on the ecology and behaviour of the elephants in the park during the years 2000–2011, the first author recorded the male–female sex ratio of the elephants as 1:4.4. In another estimation carried out by the Uttarakhand Forest Department in the year 2015, the male–female sex ratio of the elephants was found as 1:2.4. All these figures, if taken into account, reveals that the park consists of a healthy sex ratio of elephants.

It is now widely acknowledged that the elephants are intelligent and learning to adapt to their changing natural environments. Such adaptations in elephants not only make them less vulnerable to changing environment but also support other animals in maintaining their existence during severe environmental conditions.

The Rajaji National Park has been one of the potential natural habitats for tigers in north India. In fact, historical account reveals that entire terai and bhabhar tract including the foothills of the Shivaliks once consisted of a healthy population of tigers. However, since the last 4–5 decades, the population of tigers was recorded as shrinking mainly due to the habitat fragmentation. In the Park, tigers are mainly concentrated in eastern axis and only few individuals are remaining in southwestern axis. This is mainly because of disconnectivity of habitats and larger landscapes. As per an estimation carried out by the Wildlife Institute of India, the population of tigers in the Rajaji National Park was about 15 in the year 2011, which is almost stable. A study carried out on the status of tiger and leopard in the Rajaji–Corbett Tiger Conservation Unit during 1999–2000 revealed that tigers are not utilizing the west bank of the Ganga River, that is, the southwestern part of the park. This study indicated that there could be 6–10 adult tigers in the entire 1500 km2 habitat block, which includes the forest divisions of Shivalik, Dehradun, Narendranagar, and Rajaji–Motichur area of the Rajaji National Park. Since the last two decades, the Park has witnessed a stable population of tigers, though the Park has been considered as a favourable breeding ground for tigers. As Lansdowne and Haridwar Forest Divisions adjoin the park, therefore based on landscape-level planning a feasible habitat management proposal could be formulated to strengthen tiger movement across the Rajaji–Corbett wildlife corridors.

Rajaji National Park has a huge potential for bird-watchers, as a large number of winter migratory birds arrive in the reserve every year, especially at the onset of winter (from mid-October to November) and stay in different locations of the reserve until the onset of summer. Most of the winter migratory birds arrive from parts of central China/Tibet, south Siberia, central and south Asia and some other countries having extreme cold climatic conditions, especially during winter. Besides this, some bird species from Himalayan region also arrive in the reserve during the winter. Since the last one decade, large flocks of migratory birds were observed decreasing. Climate change and anthropogenic activities in roosting sites were some of the causes observed, which affected bird migration in the northwestern Shivalik landscape.

Pallas's fish eagle (Haliaeetus leucoryphus), Eurasian teal (Anas crecca), gadwall (Anas strepera), mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), northern pintail (Anas acuta), red-crested pochard (Netta rufina), ruddy shelduck (Tadorna ferruginea), bar-headed goose (Anser indicus), black-necked stork (Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus), black stork (Ciconia nigra), painted stork (Mycteria leucocephala), Pallas's gull (Ichthyaetus ichthyaetus), black-headed gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus), western yellow wagtail (Motacilla flava), Himalayan Griffon (Gyps himalayensis), darter (Anhinga melanogaster), wood sandpiper (Tringa glareola), great-crested grebe (Podiceps cristatus), and demoiselle crane (Grus virgo) are some common migrant birds reported in the Rajaji National Park. The Ganga River flows across the reserve and some of the small islands are also situated across the vast Gangetic plain, which provides feasible feeding grounds to these migratory species. Dudhia forest in Haridwar forest range, Jhabargarh forest in Chilla forest range and Gohri forests are some of the potential locations for observing these birds in natural environment. Besides, riparian corridors of River Ganga and its tributaries are some of the natural habitats for these winter migrants.

Gujjar Rehabilitation in Rajaji National Park

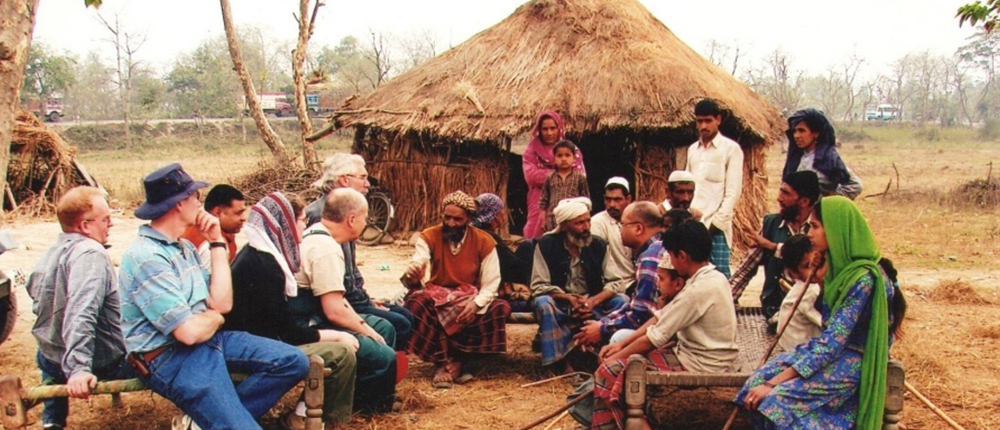

Gujjar Rehabilitation in Rajaji National Park is a model to showcase India's commitments towards biodiversity conservation. Gujjars are a nomadic pastoral community, who arrived in the Shivalik hills from the former state of Jammu & Kashmir (nowadays an Indian Union Territory) nearly 200 years ago, as part of the dowry of a princess of Nahan (at present, a part of Himachal Pradesh). In Shivaliks, they raised domestic buffalos and practised pastoralism, spending winter and the beginning of summer (from October to April) in the Shivalik foothills and peak summer and monsoon (from May to September) in the Himalayan alpine pastures. These traditional migrations generally take about 20 days to complete one-side journey from lower to higher altitude areas or from higher to lower altitude areas. Livelihood of Gujjars is primarily based on rearing buffalo and cattle, and selling milk in local markets. For achieving the objectives contained in the provisions of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, Gujjar relocation was commenced effectively in the 1980s, especially after the establishment of Uttarakhand state in November 2000.

Initial attempts were made in 1984 to resettle Gujjars (by the then Uttar Pradesh State Government, and now Uttarakhand) but the programme could not be succeeded because of non-participation of Gujjars in the programme. Besides, the fear of divesting of their traditional rights was another reason, which encouraged them not to leave the forest. With the passage of time, the programme was made more effective because of sincere and dedicated efforts by the Government and Gujjars' understanding about the benefits of urban life. This resulted in successful rehabilitation of about 98 per cent Gujjars in two different rehabilitation sites, namely Pathri and Gaindikhatta.

As a result of effective implementation of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, out of total nine forest ranges, seven ranges are completely free from Gujjars so far, which has reduced anthropogenic pressure in the Park. The programme has motivated Gujjars to lead urban life, which has considerably enhanced their livelihood and socio-economic status. Nowadays, most of their children are receiving education from schools, established by the state government at rehabilitation sites. Besides, they are cultivating some cash crops and vegetables in the land provided to each family at rehabilitation sites. Gujjar relocation in the Rajaji National Park can be considered as a model demonstration to showcase effective conservation programmes of the country, which has facilitated in achieving the objectives of the Indian Wildlife Act on one hand, and has provided better livelihood options to the pastoral Gujjars on the other hand. This conservation initiative has also ensured priorities of wildlife conservation and is a milestone to showcase the successful rehabilitation and ecological restoration model and to share conservation lessons with other range countries.

Four crucial wildlife corridors exist across the Rajaji National Park, which connect the reserve with Corbett Tiger Reserve, namely Motichur–Kansrao–Barkot (2.5 km long x 2 km wide), Chilla–Motichur (3.5 km long x 1 km wide), Rawasan–Sonanadi (10 km long x 5 km wide), and Motichur–Gohri (4 km long x 1 km wide). During 2000–2011, the movement of elephants was restricted in some of the corridors, mainly because of developmental activities. Some population of the elephants was also observed rarely using Chilla–Motichur and Motichur–Kansrao–Barkot corridors. However, the elephants were observed using the Rawasan–Sonanadi corridor on a regular basis. The widening of the Haridwar–Dehradun national highway, which exists across the reserve to four lanes, would affect the movement of elephants across the Motichur–Chilla, Motichur–Gohri and Motichur–Kansrao–Barkot wildlife corridors. Keeping in view the importance of biodiversity and animal movement across these corridors, efforts are also being made to provide the animals with a natural connectivity to move across larger landscapes. Four flyovers are under construction (each ~0.5 km long) in different animal-crossing areas, which lie within the Motichur–Kansrao and Motichur–Chilla corridors. In southwestern part of the Park, access of the elephants to the Ganga River, which flows within the park area, has been restricted, mainly because of the presence of a national highway, railway track, and human settlements. Some recognized bulls used to move across Ganga occasionally by crossing the populated area and national highway and railway track. However, the movement of the elephant groups has almost been restricted in this part. In eastern part of the Park, movement of the elephants along the Ganga River could be seen in summer when their movements are confined nearer to the riparian corridors.

Today, since most of the wild animals are listed under various Schedules of the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972, Appendices of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and in the Red List of Threatened Species of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the future survival of the wildlife in the Rajaji National Park largely depends on effective management and conservation approaches. Moreover, local community and stakeholder's participation in conservation initiatives and habitat's monitoring would be an effective management and conservation strategy.

In north-west India, Rajaji National Park is one of the crucial protected areas, which is a stronghold of Asian elephant population with approximately 17.19 per cent of its overall population in Uttarakhand. The undulating tropical moist deciduous and mixed forests and vital upper Gangetic plains further enhance the significance of this protected area. In such a situation, providing a natural connectivity for frequent movement of wildlife within the large landscapes is one of the major challenges, which has to be addressed on priority.

Dr Ritesh Joshi is Scientist 'E' in the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC), Government of India (GoI), New Delhi and has keen interest in wildlife conservation, protected area management, and nature education. Ms Kanchan Puri is Programme Coordinator in Environment Education Division, MoEFCC, GoI, New Delhi having deep interest in biodiversity conservation and environment education.

This article was first published in TerraGreen online magazine.