There is a need for identifying aspects of enhancing liveability that can be mainstreamed at the Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) level, which can further transform the floating concept of 'liveability' into a tangible reality.

The concept of 'liveability' has been present for a few decades; and its commonly accepted features promote the socio-cultural, economic and mental wellbeing of citizens. Improving the quality of life of citizens is also an important objective of the current urban missions of Indian cities, such as of the Smart Cities Mission and AMRUT. However, a relevant challenge has been the adaptation of this global concept into the Indian context and mainstreaming it into the urban policy and planning framework of the cities. Through initiatives such as the Ease of Living Index 2018 of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA), urban practitioners and policy-makers along with the Government of India are now actively working towards the reality of enhancing the liveability of Indian cities.

"A livable community is one that is safe and secure, has affordable and appropriate housing and transportation options, and offers supportive community features and services. Once in place, those resources enhance personal independence; allow residents to age in place; and foster residents' engagement in the community's civic, economic, and social life." – AARP Public Policy Institute (2017)

What is 'Liveability'?

The 'Liveability' concept was popularized for cities in 1999 with the Gore/Clinton Livability Agenda and gained momentum as a framework for "new tools and resources to preserve green space, ease traffic congestion, and pursue regional 'smart growth' strategies" (Herman & Lewis, 2017). The concept has since been developed further – based on what was considered as important features of having a balanced life. For instance, Mercer's Quality of Living Survey ranks cities based on 39 holistic factors, including economic, environmental, personal safety, health, education, transportations and other public service factors (Mercer, 2011). Moreover, the Economist Intelligence Unit's (EIU) Global Liveability Index Report 2018 ranked cities according to 5 parameters of stability, healthcare, culture & environment, education, and infrastructure (EIU, 2018). As can be observed in Table 1, the performance of the highest and lowest ranking cities in these 5 parameters can sometimes have a stark contrast due to their existing internal and surrounding external conditions.

The emphasis in the framework of Centre of Liveable Cities, Singapore, for liveable and sustainable cities is on a high quality of life which needs to be achieved alongside a competitive economy and a sustainable environment; and inculcates a focus on integrated planning and development and dynamic urban governance (Chye, 2012).

Table 1: Comparison between the highest and lowest ranking city in the Global Liveability Index Report 2018 (EIU, 2018)

| PARAMETERS |

RATING (100=Ideal) |

|

|

Vienna (Rank 1) |

Damascus (Rank 140) |

|

| Stability | 100.0 | 20.0 |

| Healthcare | 100.0 | 29.2 |

| Culture & Environment | 96.3 | 40.5 |

| Education | 100.0 | 33.3 |

| Infrastructure | 100.0 | 32.1 |

| Overall Rating | 99.1 | 30.7 |

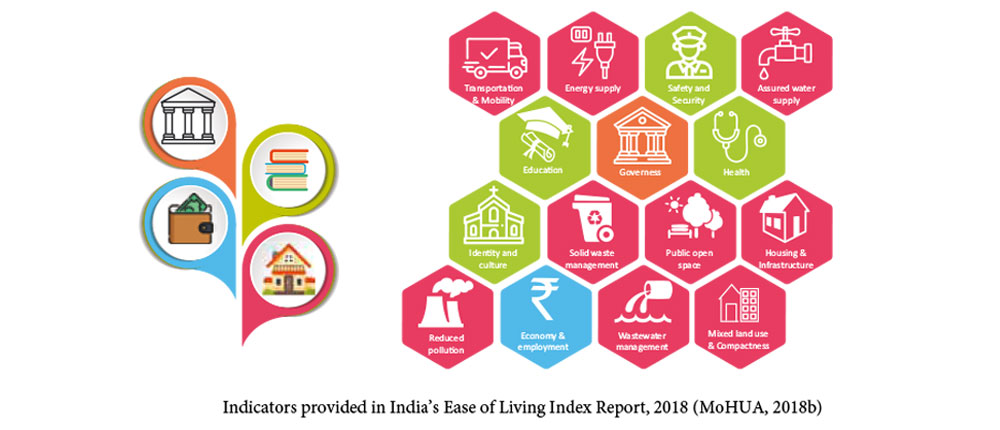

In line with the global parameters for enhancing liveability, the MoHUA of the Government of India launched the Ease of Living Index in January 2018, to support cities in systematically assessing their performance against national and global benchmarks and to work towards an 'outcome-based' approach of urban planning and policy-making. The Ease of Living Index assessed the quality of life of 111 cities (including smart cities, state/UT capital cities, and population hubs) in India across 4 pillars and 15 categories using 78 indicators, of which there were 56 core indicators and 22 supporting indicators. Interweaving the social, institutional, economic and physical pillars, this comprehensive ranking by MoHUA enabled Indian cities to take a huge leap towards imbibing liveability in their urban framework.

Key challenges and enablers of 'Liveability' for Indian cities

Urban planning and development activities in India have mostly focused on three approaches – 1) Master Plans and Town Planning schemes, wherein a city level development agenda and land use plans are prepared; 2) Centrally-sponsored National Urban Development schemes, such as the Smart Cities Missions, Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT), and Swachh Bharat Mission-Urban (SBM-U) which focus on infrastructure development and improving quality of life; and 3) International Partnerships and Funding, which include funding from international agencies and networks such as the World Bank and European Union for addressing emerging issues of environmental sustainability, climate change, infrastructure development, etc. (TERI, 2018).

However, these approaches by the central government have been considered as 'piecemeal' efforts at the city level as the centrally-sponsored urban development schemes provide ad-hoc solutions which tend to lack contextualization in some cases. There is a need for identifying aspects of enhancing liveability that can be mainstreamed at the Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) level itself which can further transform the floating concept of 'liveability' into a tangible reality.

To this end, the Regional Policy Dialogues conducted by TERI, with support from the Royal Embassy of Denmark and the International Urban Cooperation programme of the European Union (TERI, 2018), in three geographical regions of India identified key challenges and enablers based on which the urban policy and institutional frameworks of cities can be strengthened to enhance their liveability. Addressing the key challenges and issues of efficiently utilizing the enablers would ensure active engagement of stakeholders in the decision-making processes as well as help in monitoring the performance of the Indian cities.

During the focused group discussions, it was mentioned that the concept of liveability is not integrated well with existing urban planning policies and guidelines. The key parameters of liveability are generalised for all the regions but as emphasised in the dialogues, due to vast variation in the regions with respect to topography and socio-economic development, the same approach is not applicable to all the regions. There is also a lack of active citizen engagement and capacity building of the ULBs. Moreover, there is a lack of continuous funding from the central government and it was observed that there exists a wide gap between the budgeted amount and funds allocated. There is also a low presence of innovative approaches to attract public-private partnerships in the long-term risk intensive projects. The need for robust mechanisms for developing partnerships, and emphasizing clear roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders to ensure their accountability was also highlighted.

The Urban Policy and Planning aspect was considered as a key enabler for making liveable cities as it includes the need for planning at strategic and local levels and exploring suitable design concepts to promote liveability and holistic urban growth. The strengthening of Local Urban Governance incorporates the technical and financial capacity building and clear mandates to ULBs for effective service delivery and governance. In terms of Financing & Implementation, it is relevant to address the challenges of existing financial and implementation mechanisms and identifying sustainable mechanisms for meeting infrastructural demands of cities. Urban Innovation includes the promotion of innovative solutions through the private sector, research and academia participation along with improvement in institutional capacities and share knowledge between different stakeholders. The strengthening of Partnerships is thus a supplementing enabler that highlights the significance of collaborations between cities and stakeholder participation to improve the capacities of partner cities. (TERI, 2018).

Mainstreaming 'liveability' in the Indian policy framework

In order to understand the key performance indicators for liveable cities and to contextualise the understanding of liveability with respect to particular regions, TERI organised the Regional Policy Dialogues in the Southern, Eastern & North-Eastern and Western region based on the key enablers identified above. As there is vast diversity in the regions with respect to socio-economic development, geography and the challenges faced by these regions, the themes for these policy dialogues were identified based on the challenges faced by these regions. The Southern dialogue focused on the theme of "Urban Planning and Governance", the Western dialogue focused on "Infrastructure Development" and the Eastern & North-Eastern dialogue focused on "Environmental Sustainability and Climate Action" for liveable cities.

The policy dialogues were thus a medium to understand the local challenges with respect to enhancing liveability and to provide contextualized inputs to the National Urbanization Policy being drafted by MoHUA. The objective was to bring the ULBs and other stakeholders on the same platform to discuss the barriers in achieving sustainable urban development and to explore innovative mechanisms for effective implementation. The policy dialogues were also aligned with the national urban missions to encourage capacity building and active participation of implementers, academia and other think tanks and mainstream liveability of cities.

Way forward for Indian cities

The key recommendations that were provided in the Regional Policy Dialogues (TERI, 2018) to inculcate and continue working towards the 'liveability' concept in Indian cities were, first and foremost, to give high priority to mainstream the liveability pillars and indicators in the urban planning and policy framework of India. Further, it is relevant to develop urban planning frameworks and guidelines that have space for contextualized approaches of cities and can be adapted easily. There is also a need to integrate citizen participation and capacity building of the ULBs as mandatory mechanisms to achieve liveability in Indian cities. In order to ensure the least disruption in implementation and monitoring processes, consistent funding options and technical training need to be provided. The development of city-to-city partnerships and active stakeholder participation at both the international and national levels would supplement these urban mechanisms to provide an avenue for exploring innovative solutions. Such sustainable solutions would thus imbibe the 'liveability' concept in the urban policy framework of India.

References:

- AARP Public Policy Institute. 2017. Introduction. AARP Policy Book 2017-2018. Accessed from: https://policybook.aarp.org/policy-book/livable-communities/chapter-9-introduction

- Chye, K. T. 2012. The CLC framework for Liveable and Sustainable Cities. Urban Solutions, Issue 1, 58-63.

- 2018. The Global Liveability Index Report 2018. The Economist. https://www.eiu.com/public/topical_report.aspx?campaignid=Liveability2018

- Herrman, T. and Lewis, R. 2017. Research Initiative 2015-2017: Framing Livability - What is Livability? University of Oregon. Available online at https://sci.uoregon.edu/sites/sci1.uoregon.edu/files/sub_1__what_is_livability_lit_review.pdf, last accessed on October 17, 2018

- 2011. The 2011 Quality of Living Worldwide City Rankings – Mercer Survey [online] http://www.mercer.com/qualityoflivingpr#city-rankings (accessed 2018).

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA). 2018b. Ease of Living Index 2018 Report. Government of India.

- 2018. Making Liveable Cities: Challenges and Way Forward for India. Policy Brief, TERI Regional Policy Dialogues.

This article was first published in December 2018 issue of Shashwat, the annual GRIHA magazine.