With no source of income in the COVID-19 lockdown, an unprecedented migrant crisis unfolded in India. Government aid can reduce the impact of coronavirus pandemic on the food security of migrant workers.

India faces a double whammy of undernutrition and overnutrition with the prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies. The underlying cause of malnutrition is an unhealthy diet or lack of accessibility, availability and affordability of food. The poor diet has been identified as a modifiable risk factor and a leading cause of disease and death across the globe, especially in developing countries[1]. This malnutrition increases the susceptibility to infections and weakens the immune system and starts a vicious cycle. Therefore, malnutrition has been identified as one of the underlying risks for the severity of the novel coronavirus[2].

A vicious cycle of malnutrition, infection, and food insecurity

In a country like India, where around 194 million people go hungry every single day[3], controlling the spread of such a virus is a challenge in itself. Most of the population lacks the accessibility and affordability for sufficient and nutritious food to maintain their immunity. More than 50% of children and women (15- 49 years) are among the economically disadvantaged people in India i.e. belonging to scheduled castes and tribes are anaemic[4]. Individuals who suffer from food insecurity are more likely to have poorer health, and socio-economically poor background. Most of India's workforce (around 92%) is informal, including domestic servants, construction workers, vegetable vendors, etc. Many of these labourers are internal migrants (approx. 450 million) forming the backbone of India's informal sector and micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Undernutrition and food insecurity is a major problem among this migrant population, especially women and children.

Lockdown increased food insecurity

With no source of income in the COVID-19 lockdown, an unprecedented migrant crisis unfolded in India. Since some daily wage jobs cannot be performed at home, so these workers are experiencing loss of livelihoods, uncertain job prospects post lockdown, and an arrested income flow affecting them and their households [5]. The separation of urban wage workers from their income sources due to travel restrictions, they along with their families headed back to their villages already suffering from food insecurity and thus, cutting down on nutrition. The majority of villagers are reducing spending on food, buying more grains and staples in bulk at low cost instead of more expensive goods like meat and produce[6].

Therefore, their nutrition security is compromised with more consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods. In order to provide a hope of security to their families, millions of migrant workers, by any means possible, in other states started moving for their homes, no matter how far away. Due to the unavailability of any transport, many opted to walk or cycle hundreds of kilometres to get home. The different phases of lockdown have resulted in deaths of migrant workers with maximum fatalities in Phase 3 of lockdown as given below:

| Phases of Lockdown | Number of migrant deaths |

| Phase 1: March 25 - April 14 | 25 |

| Phase 2: April 15 - May 3 | 17 |

| Phase 3: May 4 - May 17 | 118 |

| Phase 4: May 18 - May 31 | 38 |

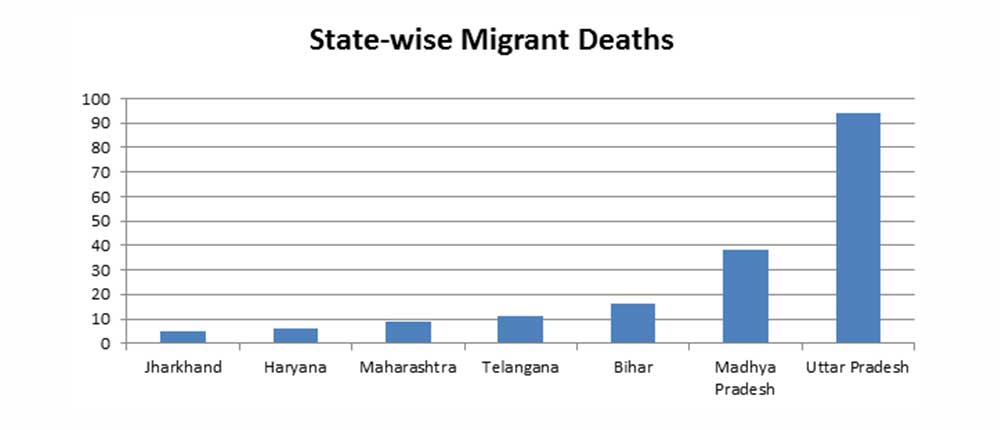

The state-wise distribution of migrant deaths is shown below[7]

Another contributor to food insecurity is halted transportation which led to the limited access of farmers to seeds, fertilisers, and insecticides. This further impacted the harvest and affected the marketing in terms of the inability of fresh produce to local and urban markets. Thus, this decreased food availability in the market, especially for poor people. The panic buying was a common phenomenon observed after lockdown for the middle class and higher-income people. But these daily wage earners were unable to stock up at that time also and then faced the price escalation which further increased their food insecurity.

Government aid to migrants

The Government of India announced the relief package with measures to help alleviate the adverse impacts on the most vulnerable segments of the population. Pradhan Mantri Gareeb Kalyan Yojna (PMGKY) targeted to provide relief to these people by ensuring food security via the government's public distribution system (PDS), and social security benefits including cash-based aid via Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT). The home delivery of cash and pensions by India Post is another measure considered to support the vulnerable populations and hence, widen the safety net for the poorest of the poor.

The state and central governments should emphasise on communicating these relief measures clearly and widely amongst the population and facilitation of easy access should be done. This will ensure the provision of essentials such as income and nutrition, as well as effectively disseminating the means to access these benefits, in managing the pandemic. Digital infrastructure is the foundation for the successful implementation of direct benefits under PMGKY for these migrant workers. This in itself poses a massive operational and logistical challenge for the government and the financial services sector, making it essential to be addressed. At the same time, this may fail to service those individuals without bank accounts resulting in large scale exclusion from accruing any social security benefits.

Another obstacle in availing benefits of these social safety schemes is the domicile restriction especially of the migrant workers. Even after the lockdown, this migrant labour will face uncertainty in employment prospects compounded by an economic slowdown affecting their food security.

Our recommendations to decrease the impact of current COVID-19 crisis on the food security (without compromising the nutritional quality) of these migrant workers include:

- Dissemination of information on schemes and service points such as community stores as cash in/ out points, digital financial touch points and PDS delivery agents.

- Elevating the coverage of government programmes such as PDS, ICDS, MDM[8] along with improvement in the nutritional quality of the foods provided through these programmes such as provision of nutritious ready- to- eat or processed foods to children, emphasis on distribution of pulses, vegetable oil under PDS

- Encouraging the religious and charitable organizations to increase their routine of free cooked meals to the poor.

- Awareness generation of the migrant workers about hygiene and sanitation who could act as change agents promoting the adoption of hygienic practices in their communities/ villages.

- More investment in public health and hygiene is required by all states to fight against the pandemic in an effective manner.

- Improved documentation as well as amendments in existing regulations on the visibility of migrant labourers.

- Adopting Kerala Model of handling COVID-19 could be advantageous. This includes a focus on prompt and multilingual information dissemination using popular media like WhatsApp, a testament to the importance of creating awareness around state response and relief efforts, which can help in reducing misinformation and thereby curbing migrant discontent.

- In the long run, the gaps in financial services need to be targeted especially towards low- income households and workers engaged in informal sector.

NGOs and community-based organizations that work closely with migrant workers can play a significant role in timely dissemination of information on schemes. Kerala launched a campaign mode to mobilise people for a variety of activities ranging from 'break the chain' campaign to set up community kitchens. The other states could use the example of Kerala to support migrant workers.

Footnotes:

[1] Global Burden of Disease 2017; https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)32279-7/fulltext#articleInformation

[2] Shekar M and Okamura K; Nutrition and COVID-19: Malnutrition is a threat- multiplier; World Bank; https://globalnutritionreport.org/blog/nutrition-and-covid-19-malnutrition-threat-multiplier/

[3] TWC India team, 2019, agricultural wastage is the leading cause of hunger in India; https://weather.com/en-IN/india/news/news/2019-09-06-agricultural-wastage-leading-cause-hunger-india

[4] International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF 2017. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015- 16, India. Mumbai: IIPS http://rchiips.org/NFHS/factsheet_NFHS-4.shtml

[5] Shashank Shreedharan and Jithin Jose; May 2020; Support for India's migrants during COVID-19: Navigating potential gaps in the system; https://www.centerforfinancialinclusion.org/support-for-indias-migrants-during-covid-19-navigating-potential-gaps-in-the-system

[6] Swinnen J; April 2020; Will COVID-19 cause another food crisis? An early review; http://www.foodsecurityportal.org/will-covid-19-cause-another-food-crisis-early-review

[7] Pushkar Banakar; 2020; Most migrants died during COVID-19 lockdown 3.0: SaveLife Foundation; https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2020/jun/03/most-migrants-died-during-covid-19-lockdown-30-savelife-foundation-2151565.html

[8] PDS: Public Distribution System; ICDS: Integrated Child Development Services Scheme; MDM: Mid- Day Meal Programme