In this article, Anita Khuller says that with increasing news of areas facing water shortages and drought, saving water and using it more efficiently has become the need of the hour. Globally, providing clean drinking water is becoming a bigger challenge with population growth. To avert this challenge, the Government of India launched the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) in August 2019 to provide safe drinking water to all rural households by 2024. JJM focuses on 1592 water-stressed blocks in 256 districts. The programme will also implement source sustainability measures as mandatory

Earth is the only known planet in the universe that has water and life. But even though 70 per cent of the planet is covered with water, only 1 per cent is easily accessible. Given that all life forms are dependent on water; its importance cannot be understated for domestic and agricultural use. In addition, water is used to produce power and in process industry.

With increasing news of areas facing water shortages and drought, saving water and using it more efficiently has become the need of the hour. Globally, providing clean drinking water is becoming a bigger challenge with population growth.

Facts and Figures

As per Dr Rajiv Kumar, Vice Chairman, National Institution for Transforming India (NITI) Aayog in August 2021, 1st in India the annual available water after evapotranspiration is 1999 billion cubic metres (bcm), of which the utilizable water potential is estimated at 1122 bcm. India is the largest groundwater user in the world, with an estimated usage of around 251 bcm per year, more than a quarter of the global total. With more than 60 per cent of irrigated agriculture and 85 per cent of drinking water supplies dependent on it, and growing industrial/urban usage, groundwater is a vital resource. It is projected that the per capital water availability will dip to around 1400 cum in 2025, and further down to 1250 cum by 2050.

A report titled “Composite Water Management Index (CWMI)”, published by NITI Aayog in June 2018, mentioned that India was undergoing the worst water crisis in its history; that nearly 600 million people were facing high to extreme water stress; and about 200,000 people were dying every year due to inadequate access to safe water. The report further mentioned that India was placed at the rank of 120 amongst 122 countries in the water quality index, with nearly 70 per cent of water being contaminated. It projected the country’s water demand to be twice the available supply by 2030, implying severe scarcity for hundreds of millions of people and an eventual loss in the country’s GDP.

The CWMI was conceptualized as a tool to instill a sense of cooperative and competitive federalism among the states. This was a first-ever attempt at creating a pan-India set of metrics that measured different dimensions of water management and use across the lifecycle of water. The water data collection exercise was carried out in partnership with the Ministry of Jal Shakti, Ministry of Rural Development, and all the States/Union Territories (UTs). The report was widely acknowledged and provided guidance to States on their success areas, absolutely and relatively, and on recommendations to secure their water future.

CWMI 2.0, released in August 2019, ranked various states for the reference year 2017–18 as against the base year 2016–17. Gujarat held on to its first rank in 2017–18, followed by Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Goa, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. Amongst North Eastern and Himalayan States, Himachal Pradesh was adjudged on top. The UTs submitted their data for the first time, with Puducherry declared the top ranker. In terms of incremental change in index (over 2016–17), Haryana held the first position in general States and Uttarakhand amongst North Eastern and Himalayan States. On an average, 80 per cent of the states assessed on the Index over the last three years have improved their water management scores, with an average improvement of +5.2 points.

But worryingly, 16 out of the 27 states still score less than 50 points on the Index (out of 100), and fall in the low-performing category. These states collectively account for ~48 per cent of the population, ~40 per cent of agricultural produce, and ~35 per cent of the economic output of India. Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Kerala, and Delhi, 4 of the top 10 contributors to India’s economic output and accounting for over a quarter of India’s population, have scores ranging from 20 points to 47 points on the CWMI. Food security is also at risk, given that large agricultural producers (states) are struggling to manage their water resources effectively. This is troubling given that assessment on almost half of the Index scores is directly linked to water management in agriculture.

On the positive side, greater focus on water governance and increased data discipline amongst states is building a pathway for driving long-term success.

Taking Action

Scientific management of water was increasingly recognized as being vital to India’s growth and ecosystem sustainability. This led to the creation of the Ministry of Jal Shakti in May 2019 under the guidance of Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi, to consolidate interrelated functions pertaining to water management, as formed by the merger of the Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation, and Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation.

On July 1, 2019, Jal Shakti Abhiyan—a campaign for water conservation and water security—followed, along with the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) launched in August 2019 to provide safe drinking water to all rural households by 2024. JJM focuses on 1592 water-stressed blocks in 256 districts. The central government has approved INR 3.6 trillion for providing piped water supply to every household. The Mission also involves the development of piped water supply infrastructure, reliable supply sources, water quality and treatment plants, training and R&D. On March 22, 2021 the second phase of JJM was launched with special emphasis on rainwater harvesting.

JJM (Urban), launched under the Union Budget 2021–22, aims to provide universal coverage of water supply to all households through functional taps in all 4378 statutory towns, while sewerage/septage management in 500 Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) cities is the other focus area. The total outlay proposed for JJM (Urban) was INR 2.87 trillion, which included INR 100 billion for AMRUT Mission. For UTs and North Eastern/Hill States, there will be 100 and 90 per cent Central funding, respectively. Meanwhile, Central funding will differ for cities, depending on their population size.

The Union Housing and Urban Affairs Ministry on February 16, 2021 launched a survey to collect data on drinking water in 10 cities under JJM (Urban) through a pilot ‘Pey Jal Survekshan’. Data on drinking water, wastewater management, non-revenue water, and condition of water bodies in the cities, is being collected through interviews with citizens and municipal officials. On the basis of learnings of the pilot survey, the exercise will be extended to all AMRUT cities.

A status report shared by the Jal Shakti Ministry in December 2021 said the JJM had already met 45.2 per cent of its target, with states such as Goa, Telangana and Haryana ensuring 100 per cent tap water connections for all rural households. The Centre and state governments have provided potable tap water connections to about 8.69 crore rural households under JJM.

Water–Health Nexus

Other problems such as water-borne diseases had to be tackled as well. Acute Encephalitis Syndrome (AES) due to Japanese Encephalitis Virus (JEV) was clinically diagnosed in India for the first time in 1955 in Tamil Nadu. During 2018, over 10,500 AES cases and 632 deaths were reported from 17 states (mainly from Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Manipur, Meghalaya, Tripura, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh) to the National Vector Borne Diseases Control Programme in India, with a case fatality rate of around 6 per cent.

So, the JJM focused on providing safe tap water supply to more than 97 lakh households in five priority states—Assam, Bihar, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal. It envisages the supply of 55 litres of water per person per day to every rural household through the Functional Household Tap Connections scheme by 2024. By working together with the health, education, social justice and housing ministries, the Water Ministry hopes to reduce AES morbidity and mortality.

JJM Highlights

As per a comprehensive report released on October 2, 2021, the following are the major achievements since 2019:

1. 8.26 crore (43 per cent) rural households (in over 1.16 lakh villages and 79 districts) are getting tap water supply in their homes

2. 5.03 crore tap water connections provided since the JJM launch

3. Goa, Haryana, Telangana, A&N Islands, Daman & Diu, Dadra & Nagar Haveli, and Puducherry have achieved ‘Har Ghar Jal’

4. 1.22 crore (36.09 per cent) households in socio-economically backward districts are getting tap water supply in their homes, that is, about four times increase in coverage since JJM was announced

5. 1.15 crore (37.83 per cent) households in 60 identified JE/AES endemic districts are getting tap water supply in their homes, that is, about 15 times increase in coverage since the announcement of JJM

6. 3.43 lakh Village Water Sanitation Committees/Pani Samitis constituted/made functional

7. 2.86 lakh Village Adoption Programmes by the National Institute of Food Technology

8. Entrepreneurship and Management students, prepared and approved in different villages

9. 7.93 lakh (76.93 per cent) schools and 7.65 lakh (68.21 percent) Anganwadi Centres provided with tap water connections.

As per MoneyControl, on February 1, 2022, India’s Finance Minister in the 2022–23 budget, earmarked INR 60,000 crore for the JJM that aims to provide potable water to 3.8 crore households in 2022–23. This was higher than the allocations of INR 115 billion in 2020–21 to INR 500.11 billion in 2021–22.

Skilling

JJM provides huge employment opportunities in villages, to successfully implement the Mission and ensure long-term operation and maintenance of in-village water supply systems. To meet this present and future requirement, skilling is a major component to produce a good number of masons, plumbers, electricians, pump operators, etc. Development partners are being engaged by states to prepare modules for sensitization and capacity building in villages. Also, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to reverse migration of skilled and semi-skilled human resources, which can be turned into a mutually beneficial opportunity for the programme and employment opportunities in rural areas.

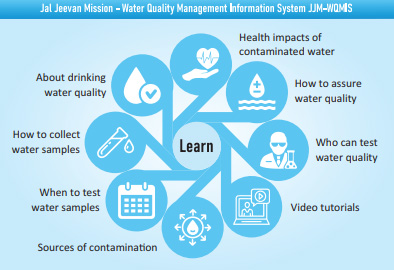

Among the technological interventions, a modern, public, online ‘JJM— Integrated Management Information System’ has been set up for day-to-day planning, implementation, monitoring, and reporting of the national/State/UT/district/village-level progress. Furthermore, to ensure transparency and modern fund management, a Public Finance Management System has been made compulsory under JJM.

In December 2020, the Ministry recommended the adoption of Internet of Things-based JanaJal Water on Wheels (WOW) to States and UTs. Monitored by GPS, JanaJal WOW is a battery-operated three-wheeler with zero carbon emissions. It also uses an innovative anti-counterfeiting technology-based solution to prevent unauthorized refilling of water and ensures delivery of safe drinking water complying with the Bureau of Indian Standards and World Health Organisation standards. The Ministry also claims that untreated water remains one of the major causes of COVID-19 and hence, availability and access to safe drinking water has become a necessity. At present, the JanaJal manages over 750 water ATMs and safe water points in association with other agencies.

Success Story

Many success stories have been highlighted over the past few years. One such example is Rajasthan, the largest state of the country with very little rainfall. It has an area of 343 lakh hectares, of which 168 lakh hectares is arable land. The Thar desert occupies around 60 per cent of the state.

The state’s Mukhya Mantri Jal Swavlambhan Abhiyan, launched in 2016, is a multi-stakeholder programme that aims to make villages self-sufficient in water through a participatory water management approach. It focuses on converging various schemes to ensure effective implementation of improved water harvesting and conservation initiatives. Use of advanced technologies such as drones to identify water bodies for restoration is one unique feature of the programme. Gram Sabhas in villages are responsible for budgeting of water resources for different uses, providing greater power to the community members in decision-making.

After the first phase itself there was 56 per cent reduction of water supply through tankers and an average rise in the groundwater table by 4.66 feet in 21 non-desert districts of the states. 50,000 hectares of additional land had been made fit for cultivation in the districts and 64 per cent of the installed hand-pumps had been rejuvenated.

Conclusion

In rural areas in India, out of total available freshwater, about 5 per cent is used for drinking and domestic purposes, 10 per cent for industrial, and 85 per cent for agricultural purposes. All water is received from precipitation during limited rainy days or snowfall, and this water is stored either over- or underground. To achieve water security, there is no choice except to focus on rainwater harvesting, recharge of aquifers, proper storage, and efficient utilization.

This conscious thought-process is to be developed in all stakeholders through education and awareness, working from schools and villages upwards. In this regard, a compendium was released by NITI Aayog in October 2021 on the role of communities in water management, and lists out best practices on: agriculture; groundwater management; watershed development; water infrastructure; and climate risk and resilience.

We also need to learn from other countries’ successes, such as Israel—it has turned a water crisis into an opportunity even though it receives one-fourth of the rainfall we get in India. Israel is now water secure and its groundwater level is also increasing, due to the adoption of new techniques.

Unless every person conserves water (which will also reduce electricity) and protects our water sources, our future generations will not survive. Whether it is simple conservation methods at home or while farming; let us all pledge to share this responsibility and take action, particularly on this World Water Day on March 22, before it is too late.

Anita Khuller has over 22 years of experience in technical writing/editing, new business development, communications/training, and capacity building in multi-national non-profit and consultancy sectors in South and Southeast Asia, in the clean energy, waste, environment, infrastructure, rural development and education areas.

Footnote:

Source: Compendium on Best Practices in Water Management 2.0 (Oct 2021)